Economic Impact of Tariff Removal between Zimbabwe, the US, and the EU

1. Introduction

Zimbabwe has recently made a bold move in trade liberalisation, dramatically altering its trading relationships with major Western economies. In early April 2025, Zimbabwe’s President Emmerson Mnangagwa announced the suspension of all import tariffs on goods from the United States in what was described as a goodwill gesture towards Washington. This came just days after the U.S. imposed an 18% duty on imports from Zimbabwe, part of a wave of tariffs introduced by the Trump administration. Around the same time, the European Union revealed it has scrapped all duties and quotas on Zimbabwean exports, effectively granting Zimbabwe full duty-free access to the EU market. These parallel developments, Zimbabwe dropping tariffs on American imports and the EU eliminating tariffs on Zimbabwe’s exports, signal a substantial move toward greater trade liberalisation. They raise important questions about the economic impact on Zimbabwe and its partners.

From a broad perspective, such steps signal greater integration of Zimbabwe into global trade networks. Removing tariffs is expected to lower trade barriers and potentially boost the flow of goods. This reflects classic trade liberalisation theory, reducing tariffs tends to lower prices, increase trade volumes, and improve overall economic welfare by allowing each country to specialise in what it produces most efficiently. Zimbabwe’s policy changes fit into a global context of trade negotiations and align with the economic partnership agreements already in place For instance, Zimbabwe has been part of an EU-Eastern and Southern Africa interim Economic Partnership Agreement since 2012. However, realising the benefits of trade liberalisation involves trade-offs and adjustments. In the short term, Zimbabwe’s government stands to lose tariff revenue, and local firms may face stiffer competition. In the longer term, access to larger markets and cheaper inputs could drive productivity gains, industrial growth, and greater competitiveness for Zimbabwean products. The following sections analyse the impact from multiple perspectives, like government, local firms, American exporters, Zimbabwean exporters and explore strategic opportunities arising from these tariff removals.

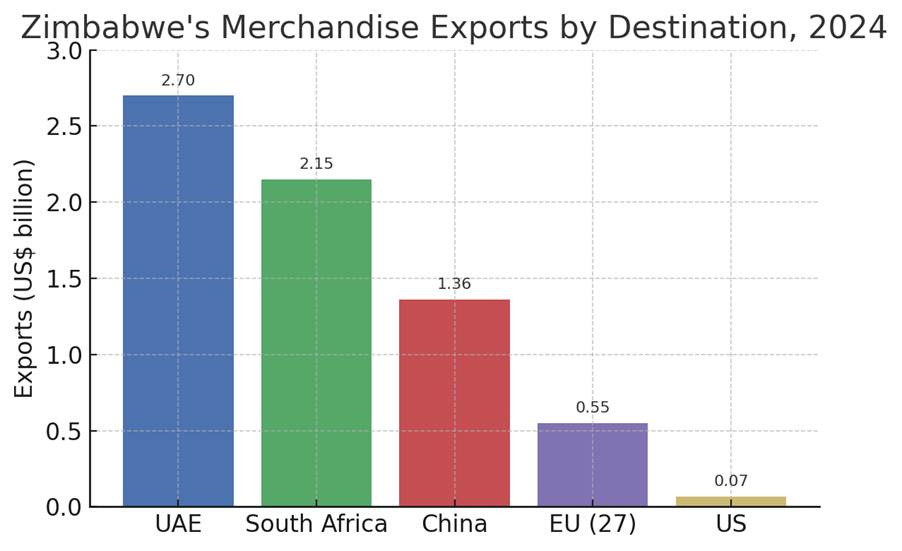

Figure 1: Zimbabwe’s exports by major destination in 2024 (US$ billions).

Notes: The UAE, South Africa, and China together accounted for over 80% of export earnings, approximately US$2.7 bn, $2.15 bn, and $1.36 b,n respectively, whereas the entire EU market made up only around 7% that is $0.55 bn and the US under 1%. The new tariff policies aim to bolster trade with the US and EU from these relatively low baselines.

2. Government Perspective, Revenue Trade-Off vs Long-Term Gains.

From the Zimbabwean government’s perspective, the removal of import tariffs on U.S. goods presents an immediate fiscal trade-off. Tariffs have historically been an important source of public revenue, especially in developing economies. By scrapping duties on American imports, the government forfeits short-term income it would have collected at the border. Given that until now most goods entering Zimbabwe faced around a 15% import levy, this policy means cheaper imports for consumers but a direct hit to the Treasury. For example, U.S. exports to Zimbabwe were about $43.8 million in 2024. If similar volumes continue, eliminating a roughly 15% tariff could cost the government on the order of several million US dollars per year in lost tax revenue. In a country often grappling with budget deficits, inflation, and funding shortages for public services, even this relatively modest sum is not trivial. Policymakers must weigh this fiscal loss against potential benefits that are more diffuse and long-term in nature.

The government is effectively betting that the long-term gains from freer trade will outweigh the short-term revenue sacrifice. Access to cheaper American technology and capital goods, such as smartphones, computers, heavy-duty machinery and industrial equipment, can help local industries modernise at a lower cost. This can spur productivity growth across sectors. According to international trade theory, reducing tariffs on inputs and capital goods can have an outsized impact on productivity. For instance, an IMF study found that a 1 percentage-point cut in input tariffs can raise total factor productivity in the importing sector by about 2% (Ahn et al., 2016). Applied to Zimbabwe, removing taxes on U.S. machinery and equipment could lower production costs for Zimbabwean manufacturers and farmers, enabling them to produce more efficiently and competitively. Over time, this productivity boost could expand the overall economic pie, growing industry output, employment, and eventually the tax base through VAT, income taxes, etc., which might compensate for the initial loss of tariff revenues.

There are also diplomatic and strategic motivations behind Zimbabwe’s tariff decision. Officials signalled that scrapping U.S. import duties was intended to “build a positive relationship” with Washington after years of strained ties. By unilaterally opening its market, Zimbabwe hopes to encourage a reciprocal gesture, for example, persuading the U.S. to reconsider the newly imposed 18% tariff on Zimbabwean exports or to ease long-standing sanctions. In essence, the government is trading off a revenue stream in the hope of both economic stimulus and improved geopolitical relations. President Mnangagwa’s administration framed the move as aligning with Zimbabwe’s policy of “fostering amicable relations with all nations” rather than engaging in tit-for-tat tariff wars. This stance contrasts with many other countries that responded to U.S. tariffs with their retaliatory duties. Zimbabwe instead, is positioning itself as a cooperative partner, which could invite greater foreign investment or aid down the line.

That said, the government is aware of the risks and criticisms of this approach. Some economists have warned that completely duty-free U.S. imports might undercut local producers and flood the market with cheap goods, potentially hurting domestic industries and jobs. If local manufacturers cannot compete with untaxed American products, Zimbabwe could see factory output decline in the short run, leading to layoffs or business closures, which in turn reduces other tax revenues. Moreover, Zimbabwe’s other trading partners, like South Africa or China, might question why American goods get special treatment while their exports still face Zimbabwean import tariffs. This could strain relations or prompt those partners to demand similar concessions. The government must manage these diplomatic complexities to avoid “souring relationships with partners”. In summary, from the official perspective, removing tariffs is a calculated gamble: it sacrifices immediate income and potentially exposes local industry, but it aims to catalyse long-term economic growth, competitiveness, and goodwill that benefit Zimbabwe more substantially in the future.

3. Firm Perspective in Zimbabwe

For Zimbabwean businesses, especially import-dependent firms, the elimination of tariffs on U.S. goods is largely a welcome development. Importing from the U.S. will now be significantly cheaper, directly reducing costs for companies that rely on American products. This includes a range of sectors such as mining companies importing heavy machinery or spare parts, construction firms buying specialised equipment, manufacturers sourcing components or industrial chemicals, and retailers bringing in American electronics or consumer goods. A 15% tariff removal is effectively a 15% price cut on these inputs, assuming currency and shipping costs remain constant. Such cost savings can improve profit margins or be passed on as lower prices to Zimbabwean consumers. For example, a local agri-business that needed a $100,000 tractor from the U.S. would have paid $115,000 when the tariff was in place; now it pays just $100,000, freeing up $15,000 that could be invested in hiring more workers or buying additional inputs. In a challenging business environment often marked by high inflation and foreign currency shortages, these savings are a much-needed relief.

Access to better technology from the United States can be transformative for productivity. The U.S. is known for its advanced machinery, innovative industrial equipment, and high-quality capital goods. With tariffs gone, a wider array of American products, from precision farming equipment and food-processing machinery to medical devices and IT hardware, become affordable to Zimbabwean firms. Upgrading to modern equipment can raise the efficiency of production processes in Zimbabwe. For instance, a Zimbabwean textile manufacturer could import state-of-the-art sewing machines or fabric looms from the U.S., enabling faster production with less waste. A mining firm could obtain more efficient drilling or mineral processing equipment, increasing output for the same level of inputs. Productivity improvements like these are crucial for Zimbabwean industries to become competitive, not just domestically but also in export markets. In economic terms, the country’s production possibility frontier may expand as firms adopt cutting-edge technologies, allowing them to produce goods at lower unit costs. Over time, this can shift comparative advantage. Zimbabwe might find it can competitively produce certain manufactured or processed goods once its factories are better equipped.

Lower import costs on inputs also enhance the competitive positioning of Zimbabwean companies regionally. If neighbouring countries still impose tariffs on U.S. machinery or inputs, Zimbabwean firms now have a cost advantage in acquiring those resources. They could potentially produce goods more cheaply than, say, a Zambian competitor who must pay duties on the same equipment. This advantage could help Zimbabwe become a regional manufacturing or processing hub in certain niches. Moreover, by obtaining capital equipment more cheaply, Zimbabwean firms can scale up production capacity at lower capital expense. This might encourage new investments, for example, an entrepreneur considering setting up a food processing plant may find the economics more favourable now that imported American dryers or packaging machines are duty-free. The overall effect is to lower barriers to entry and expansion for businesses.

However, from the firm perspective, nuances are depending on the type of business. Import-intensive businesses like wholesalers of foreign goods or firms needing advanced inputs benefit. On the other hand, some local producers that previously faced limited competition from U.S. goods might see increased competition. For instance, if tariffs on imported American foodstuffs or consumer goods were shielding a local producer, those protections are now gone. A local company making packaging paper might now have to compete with cheaper imported paper from the U.S., coming in duty-free. This pressure can be healthy in the long run as it forces firms to improve efficiency and quality, but in the short run, some less efficient businesses could lose market share. The key for Zimbabwean firms is to seize the opportunity of cheaper inputs to upgrade and pivot toward higher-value activities. Firms that leverage new technology and know-how from abroad can improve their product offerings. Economic history shows that exposure to international competition and access to world-class inputs often drive domestic firms to innovate and become more productive, the so-called “learning by importing” effect. Zimbabwean companies that take this approach are likely to emerge more competitive, both at home and globally, as a result of these tariff changes.

4. American Exporter Perspective

From the perspective of American exporters and producers, Zimbabwe’s scrapping of tariffs on U.S. goods opens a promising market opportunity. Although Zimbabwe’s market is relatively small in absolute terms, it has unmet demand in sectors where U.S. firms have expertise. With import duties lifted, U.S. products become more price-competitive in Zimbabwe than ever before. Goods made in the USA effectively receive a tariff preference in Zimbabwe over products from other countries that still face duties. For example, a piece of agricultural machinery from the U.S. that used to be 15% costlier due to tariffs will now compete on equal footing with equipment from Europe or Asia, which might still incur some import tax. This improved price competitiveness could boost sales volumes for U.S. exporters. An American manufacturer of farming tractors or mining trucks may find it much easier to win contracts in Zimbabwe now, as Zimbabwean buyers consider the total cost, product price + tariff. American exporters of consumer goods, such as apparel or processed foods, might also see higher orders from Zimbabwean wholesalers who previously shied away due to the added tariff cost.

The removal of tariffs can also change the perception of market viability. Zimbabwean importers and distributors may actively start seeking U.S. suppliers for goods now that they know those goods can enter duty-free. This increase in interest could encourage more American companies to market their products in Zimbabwe or to appoint local distributors. U.S. firms that had not considered Zimbabwe due to its high import tariffs or its past economic instability might re-evaluate it as an emerging market with growth potential. The timing is notable; Zimbabwe’s gesture comes when the U.S. has been increasing tariffs globally, yet Zimbabwe is the only country so far to drop tariffs in response. This sets Zimbabwe apart as a very open market to American goods, which U.S. exporters could interpret as a positive signal. In trade negotiations or business forums, Zimbabwe can now advertise that American companies have an advantage in their market that others do not. Over time, this could lead to U.S. firms capturing a larger share of Zimbabwe’s import basket, diversifying Zimbabwe’s import sources, currently dominated by South Africa and China.

In concrete terms, American industries likely to benefit include those already exporting to Zimbabwe, machinery, pharmaceuticals, and agriculture. U.S. exports to Zimbabwe have been relatively small, just $43.8 million in goods in 2024, consisting mainly of industrial machinery, equipment, medicines, and some agricultural produce. These figures could grow as tariffs fall to zero. For instance, U.S. pharmaceutical companies could expand their sales of medical drugs or devices if those items become more affordable to Zimbabwe’s health sector without duties. American farmers or agribusinesses might export more grain, soybean products, or meat to Zimbabwe if their products become price-competitive against regional suppliers. Furthermore, U.S. technology and electronics firms, from computer hardware to renewable energy equipment,t might find new customers in Zimbabwe’s businesses and government projects now that pricing is more favourable.

It’s important to note that Zimbabwe’s market size and currency stability remain limiting factors. U.S. exporters will gauge not just tariffs but also the broader economic context, such as inflation, foreign exchange availability, and demand levels in Zimbabwe. While tariffs are within Zimbabwe’s control, factors like currency risk or slow economic growth could still temper American enthusiasm. Nonetheless, removing the duty barrier is a critical first step to unlocking trade. Even a modest increase in U.S.-Zimbabwe trade would be significant relative to the low base. Trade between the two countries was only about $111 million in 2024, a tiny fraction of both the U.S. export market and Zimbabwe’s total trade. American businesses now have a clear incentive to increase that figure. In the long run, if U.S. companies can establish a stronger foothold, they may also become more invested in Zimbabwe’s economic development, for example, by providing training, credit terms, or even local assembly operations. Thus, from the U.S. exporter viewpoint, Zimbabwe’s tariff removal is a green light to expand sales, contribute to Zimbabwe’s import needs, and potentially build lasting commercial partnerships.

5. Zimbabwean Exporter Perspective

For Zimbabwean exporters, especially those producing agricultural and manufactured goods, the European Union’s decision to eliminate all duties and quotas on imports from Zimbabwe is a game-changer. It means Zimbabwe now enjoys completely duty-free, quota-free access to a market of 450 million consumers in the EU. While Zimbabwe has had partial preferential access to the EU under previous arrangements, this announcement confirms that any Zimbabwean company can export any product to the EU without incurring European tariffs. In practice, this offers enormous opportunities to expand export volumes and enter new product categories in Europe. Price competitiveness of Zimbabwean goods in the EU will improve because tariffs that might have added 5–15% to the cost, depending on the product,t are no longer a factor. For European importers and retailers, Zimbabwean goods become relatively cheaper, which could make them more inclined to source from Zimbabwe over other non-preferential countries.

One immediate beneficiary is Zimbabwe’s agriculture and horticulture sector, which already has a foothold in Europe. The EU is a major buyer of Zimbabwean horticultural products, including citrus fruits, berries, nuts, flowers, and vegetables. In fact, the EU currently purchases over 40% of Zimbabwe’s horticultural exports. With all duties removed, these farm exports can be priced more competitively on European supermarket shelves. For example, Zimbabwean blueberries or oranges can enter Europe at zero duty, unlike, say, similar produce from a country without such an agreement. This could boost demand from European importers for Zimbabwe’s produce, potentially leading farmers to scale up production. Moreover, new agricultural products could find a market in the EU. If previously there were quota limits or tariffs on items like sugar, beef, or processed foods from Zimbabwe, those are now lifted or significantly eased. This creates an incentive for Zimbabwean producers to explore exporting a wider range of goods from coffee and tea to essential oils, leather products, textiles, or handicrafts. This expansion will be due to zero duty at EU ports. The elimination of quotas is equally crucial; even if Zimbabwe drastically increases its exports of a particular product, it will not suddenly hit a quota ceiling and incur tariffs. Essentially, the EU has provided a blank canvas for Zimbabwe to paint its export growth story.

However, market access on paper does not automatically translate into market entry in reality. A critical challenge for Zimbabwean exporters is meeting the EU’s stringent standards and regulations. The EU is well known for its high sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) standards, technical regulations, and quality requirements. For Zimbabwean food exports, fresh or processed, complying with EU standards on pesticide residues, food safety, and traceability is mandatory. For instance, a Zimbabwean farm cooperative exporting peas or citrus must ensure their produce meets the EU’s Maximum Residue Levels for any chemicals and follows proper post-harvest handling to avoid interception at EU borders. Similarly, if Zimbabwe wants to export meat or dairy to the EU, it needs to adhere to European animal health and food processing standards, which might require significant upgrades to local slaughterhouses and cold chain facilities. Quality control and certification will therefore be a top priority. Encouragingly, the EU has recognised this need, with a €10 million Zimbabwe EPA Support Programme to aid local exporters to comply with EU standards and rules of origin requirements. This includes helping businesses get the necessary certifications, improve their packaging and labelling, and understand European regulations.

Local businesses and the government must also tackle the awareness gap. EU Ambassador Jobst von Kirchmann noted that many Zimbabwean companies are simply not aware that they have this duty-free access to the EU. There may be untapped potential in industries that have never tried exporting to Europe. A concerted effort by trade promotion agencies like ZimTrade and the Zimbabwe National Chamber of Commerce is needed to educate companies about the EU opportunity. Workshops, training on export procedures, and matchmaking with EU buyers can help translate the tariff-free access into actual deals. Additionally, Zimbabwean exporters should be strategic; duty-free access gives them a price edge, but they still must compete on quality, reliability, and marketing. For example, a Zimbabwean coffee producer entering the EU market will be competing with established suppliers from Latin America or Asia. The lack of EU tariffs is an advantage, but success will also depend on offering a high-quality product and building relationships with European importers.

The EU tariff removal can also encourage value addition for export, not just raw commodity exports. Since even processed or high-value goods are duty-free, a Zimbabwean business can export, say, organic dried fruits, jams, or canned vegetables to Europe without worrying about EU import taxes that typically escalate with value. This encourages moving up the value chain, an area where Zimbabwe has historically lagged. In fact, despite this preferential access existing for years, Zimbabwe’s exports remain dominated by raw or semi-processed commodities such as gold, nickel, tobacco, etc., with minimal value addition. Now with a fully open EU market, there is a stronger incentive for entrepreneurs to develop higher-value products for Europe, knowing that their efforts won’t be undermined by import duties. Overall, from the Zimbabwean exporter's perspective, the EU’s elimination of tariffs is a tremendous opportunity. The key is to convert this preferential access into real, sustainable export growth by investing in meeting standards, scaling production, and building the capacity to consistently supply the European market.

6. Strategic Domestic Opportunity, Marrying U.S. Inputs with EU Market Access

The simultaneous opening of Zimbabwe’s economy to cheaper imports from the U.S. and improved export access to the EU creates a unique strategic opportunity to boost domestic value addition. Essentially, Zimbabwe can leverage affordable capital goods from one partner, the U.S., to produce value-added products that it can sell to a tariff-free market in another, the EU. This triangulation could help Zimbabwe break away from the traditional extract-and-export model and develop a more industrialised, export-oriented economy at home.

Consider Zimbabwe’s abundant raw materials and agricultural produce. In the past, much of these were exported in raw form, minerals shipped out without refining, or crops sold with minimal processing. This is due to constraints in local processing capacity. Now, with U.S. machinery and equipment being duty-free, it becomes more feasible for Zimbabwean businesses to import the equipment needed to process these raw materials domestically. For example, a company that exports mangos or pineapples can import industrial dehydrators or canning machines from the U.S. at lower cost, set up a plant in Zimbabwe, and start exporting dried fruit and canned fruit to Europe. The dried fruit or canned product will fetch a higher price than raw fruit, and, thanks to the EU’s duty removal, it will enter Europe tax-free just like the raw fruit would. The value captured in Zimbabwe through processing, packaging, and possibly branding means more revenue stays in the country, more jobs are created locally in factories rather than just farms, and the export earnings per unit of raw material increase. This is how trade liberalisation can catalyse industrial development, by providing both the means in form of cheap inputs and the market access,s duty-free exports for higher-value production.

Another sector to highlight is food and agro-processing. Zimbabwe has large cattle herds and was once a major beef exporter. Instead of exporting live animals or basic cuts, Zimbabwe could invest in modern abattoirs and meat-processing facilities with equipment potentially imported duty-free from the U.S. or EU to produce packaged beef products or even processed meats like dried meats or sausages for export. The EU market, which has now removed quotas and tariffs, could be targeted if Zimbabwe meets the health standards. Similarly, Zimbabwe grows plenty of tobacco and could produce finished tobacco products like cigarettes, cigars, and e-cigarette liquids for export. While tobacco faces health-related demand issues globally, there are still markets in Europe for speciality tobaccos or nicotine products, and duty-free access gives Zimbabwe an edge over non-preferential competitors. Tea and coffee processing is another area as Zimbabwe produces tea in the Eastern Highlands. Instead of bulk tea exports, local factories can produce packaged tea bags or branded artisanal tea for EU consumers. The machinery for such factories blending packaging machines, can now be imported more cheaply from the U.S. or Europe. Recall that the EU interim EPA also allows duty-free import of EU machinery into Zimbabwe. Thus, Zimbabwe benefits on both ends input side and the output side.

Zimbabwe’s relatively low labour costs and natural resource base complement these opportunities. Labour-intensive processing that might be costly in Europe can be done economically in Zimbabwe, giving its products a cost advantage, especially now that neither labour costs nor tariff costs are adding much to the price. For instance, hand-crafted leather goods or textiles could be produced in Zimbabwe using imported American tanning chemicals or sewing equipment and then exported to Europe duty-free. We see a synergy; U.S. inputs such as technology, machinery, expertise, combined with Zimbabwe’s local inputs, labour, and raw materials, can result in competitive products for the EU. This approach aligns with development strategies that seek to integrate into global value chains where Zimbabwe can carve out roles in value chains where it adds value to its own resources. It could shift from exporting raw chrome ore to exporting ferrochrome or chrome-containing manufactured products, using imported furnaces or factory equipment with reduced cost. In mining, where Zimbabwe has minerals like lithium or platinum, acquiring U.S. mineral processing technology at a lower cost could enable more local refining and battery precursor production, aiming to supply Europe’s demand for processed minerals.

To seize this strategic opportunity, coordination between policymakers and the private sector is vital. The government can support by providing incentives for value-added industries, for example, tax breaks or loans for companies that invest in processing equipment and export finished goods. Notably, the EU has already introduced financial support, and a €60 million European Investment Bank loan facility is in place to provide long-term, low-interest loans to Zimbabwean businesses for industrial projects. This kind of funding can help overcome the initial capital hurdles. By tapping such funds and the tariff advantages, Zimbabwean entrepreneurs can set up factories for things like fruit processing, textile weaving, wood furniture making, or metal fabrication. Over time, this would diversify Zimbabwe’s export basket and reduce the vulnerability of relying on a few commodities. The country’s recent record export earnings of over $7 billion in 2024 were largely driven by minerals and tobacco, but with these new developments, future export growth could come from more sustainable, value-added sectors. In summary, the convergence of tariff-free U.S. imports and EU market access presents Zimbabwe with a window to advance industrialization, by importing the machines that add value to its raw materials and then exporting higher-value products, Zimbabwe can capture a greater share of the value chain, create jobs, and foster more resilient economic growth.

7. Conclusion

The removal of tariffs in Zimbabwe’s trade with the US and EU presents a mix of opportunities and challenges that could shape the country’s economic trajectory for years to come. On one hand, Zimbabwe stands to gain significantly from increased trade flows, enhanced productivity, and deeper integration into global markets. Consumers and firms will enjoy lower prices on imported goods and inputs, potentially improving living standards and business competitiveness. Access to cheaper American technology and equipment can address long-standing gaps in Zimbabwe’s industrial capacity, giving local producers the tools to upgrade. Meanwhile, duty-free entry into the EU offers a chance to boost exports, especially of non-traditional and value-added products, thereby diversifying Zimbabwe’s economy away from an over-reliance on unprocessed commodities. These developments resonate with international trade theory, by each country plays to its strengths. The US exports capital goods, Zimbabwe exports more of what it can produce well and trading freely, overall welfare can increase for all parties.

On the other hand, the challenges cannot be ignored. The Zimbabwean government must manage the fiscal impact of losing tariff revenues and find ways to plug that gap, perhaps through improved tax collection elsewhere or economic growth expanding the tax base. There is also the risk that domestic industries, if unprepared, could be outcompeted by a surge of duty-free imports. This calls for supportive measures such as temporary assistance or retraining programs for affected sectors, and efforts to improve the ease of doing business so local firms can become more efficient. For exporters, merely having market access is not enough; Zimbabwean products must meet high standards and be produced at scale and consistent quality. This requires investment in skills, infrastructure like reliable electricity and transport, and compliance systems. The government and private sector should work hand-in-hand to capitalise on the openings, for example, by using the EU’s support programs, by actively promoting Zimbabwe’s products abroad, and by encouraging joint ventures that bring in expertise and capital.

Zimbabwe’s decision to scrap tariffs on U.S. imports and the EU’s move to eliminate duties on Zimbabwean exports together create a rare open-door scenario. Zimbabwean businesses and policymakers should treat this as a golden window to enhance competitiveness. Firms are encouraged to import the best machinery and know-how they can afford and to venture into new export ventures, whether it is a farm cooperative starting to export canned fruits to Europe or a textile company investing in modern looms to produce apparel for international markets. Policymakers, for their part, should ensure the macroeconomic environment remains stable so that the benefits of these policies are not eroded by currency or inflation crises and continue implementing reforms that reduce other barriers to trade, such as customs logistics or red tape. By doing so, Zimbabwe can turn what might seem like a unilateral concession into a catalyst for economic modernisation and growth. The coming years will be critical, with savvy strategy and sustained effort, Zimbabwe can leverage the tariff removals to build a more productive, export-driven economy. An economy that creates jobs at home, earns valuable foreign exchange, and truly takes advantage of the goodwill extended by its international trading partners. The message to Zimbabwean enterprises is clear: now is the time to gear up, innovate, and compete on the global stage, using the platforms that zero-tariff access provides. With the right response, Zimbabwe can transform this policy shift into tangible development gains, turning challenges into opportunities for a more prosperous future.

References

Ahn, J., Dabla‑Norris, E., Duval, R.A., Hu, B. and Njie, L. (2016) Reassessing the Productivity Gains from Trade Liberalization. IMF Working Paper 16/077. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/Reassessing-the-Productivity-Gains-from-Trade-Liberalization-43828 (Accessed: 2 May 2025). IMF

Bulawayo24 News, Staff reporter (2025) ‘EU scraps duty on Zimbabwe exports’, Bulawayo24 News, 28 April. Available at: https://bulawayo24.com/index-id-news-sc-national-byo-252327.html (Accessed: 2 May 2025).Bulawayo24 News

Equity Axis News – Maurukira, S. (2025) ‘EU reaffirms duty‑free trade access for Zimbabwe’, EquityAxis, 28 April. Available at: https://equityaxis.net/post/18387/2025/4/eu-reaffirms-duty-free-trade-access-for-zimbabwe (Accessed: 2 May 2025).Equity Axis

Gahadza, N. (2025) ‘Duty‑free access to boost Zim exports to EU’, The Herald, 1 May. Available at: https://www.zimbabwesituation.com/news/duty-free-access-to-boost-zim-exports-to-eu/ (Accessed: 2 May 2025).zimbabwesituation.com

Herald Editorial Board (2025) ‘Editorial Comment: Let’s capitalise on EU duty‑free access’, The Herald, 2 May. Available at: https://www.heraldonline.co.zw/editorial-comment-lets-capitalise-on-eu-duty-free-access/ (Accessed: 2 May 2025).Herald Online

Lawal, S. (2025) ‘Is Zimbabwe wooing Donald Trump by paying white farmers and ending tariffs?’, Al Jazeera, 17 April. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/4/17/is-zimbabwe-wooing-donald-trump-by-paying-white-farmers-and-ending-tariffs (Accessed: 2 May 2025).Al Jazeera

Mnangagwa, E. [@edmnangagwa] (2025) ‘The principle of reciprocal tariffs, as a tool for safeguarding domestic employment and industrial sectors, holds merit…’ 5 April. Tweet. Available at: https://twitter.com/edmnangagwa/status/1908540082815893527

(Accessed: 2 May 2025).X (formerly Twitter)

Musarurwa, T. (2025) ‘Zim’s impressive export growth: Risks and opportunities’, The Sunday Mail, 26 April. Available at: https://www.sundaymail.co.zw/zims-impressive-export-growth-risks-and-opportunities (Accessed: 2 May 2025).herald.

United States Trade Representative (2025) Zimbabwe Trade Summary 2024. Washington, DC: Office of the U.S. Trade Representative. Available at: https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/africa/southern-africa/zimbabwe (Accessed: 2 May 2025). ustr.gov.

Disclaimer: This article is presented solely for academic and illustrative purposes. It draws on publicly available data and independent analyses to examine the potential economic effects of recent tariff changes between Zimbabwe, the United States, and the European Union. Nothing herein should be construed as official economic, legal, or policy advice, nor as a definitive statement of government strategy. Readers should seek professional guidance before making investment, trade, or policy decisions based on the information discussed.